Flora og Fjære: How a Private Island Garden Became Norway's Most Unusual Day Trip

You can't just show up at Flora og Fjære. The 12-acre garden on Sør-Hidle island accepts no walk-ins, offers no garden-only admission, and operates only four months per year. Every visitor pays around 1,890 NOK ($175 USD) for a bundled experience: boat transfer, guided tour, and three-course meal. Yet somehow, this mandatory package deal attracts 35,000 guests during its five-month season—more visitors per operating day than many Norwegian museums see in a month. The question isn't whether Flora og Fjære works as a business. It's how a private family garden on a windswept island became one of coastal Norway's most visited attractions.

From Disability Benefits to Commercial Garden

The story begins with failure, not vision. In 1965, Åsmund and Else Marie Bryn bought a barren farmstead on the northern tip of Sør-Hidle—a property so exposed to North Sea winds that previous owners had given up on agriculture. The Bryns built a small cabin but nothing more ambitious. Then in 1987, Åsmund received disability benefits and couldn't work at the family nursery business. With time but not health, he began planting pine trees as windbreaks and experimenting with exotic species.

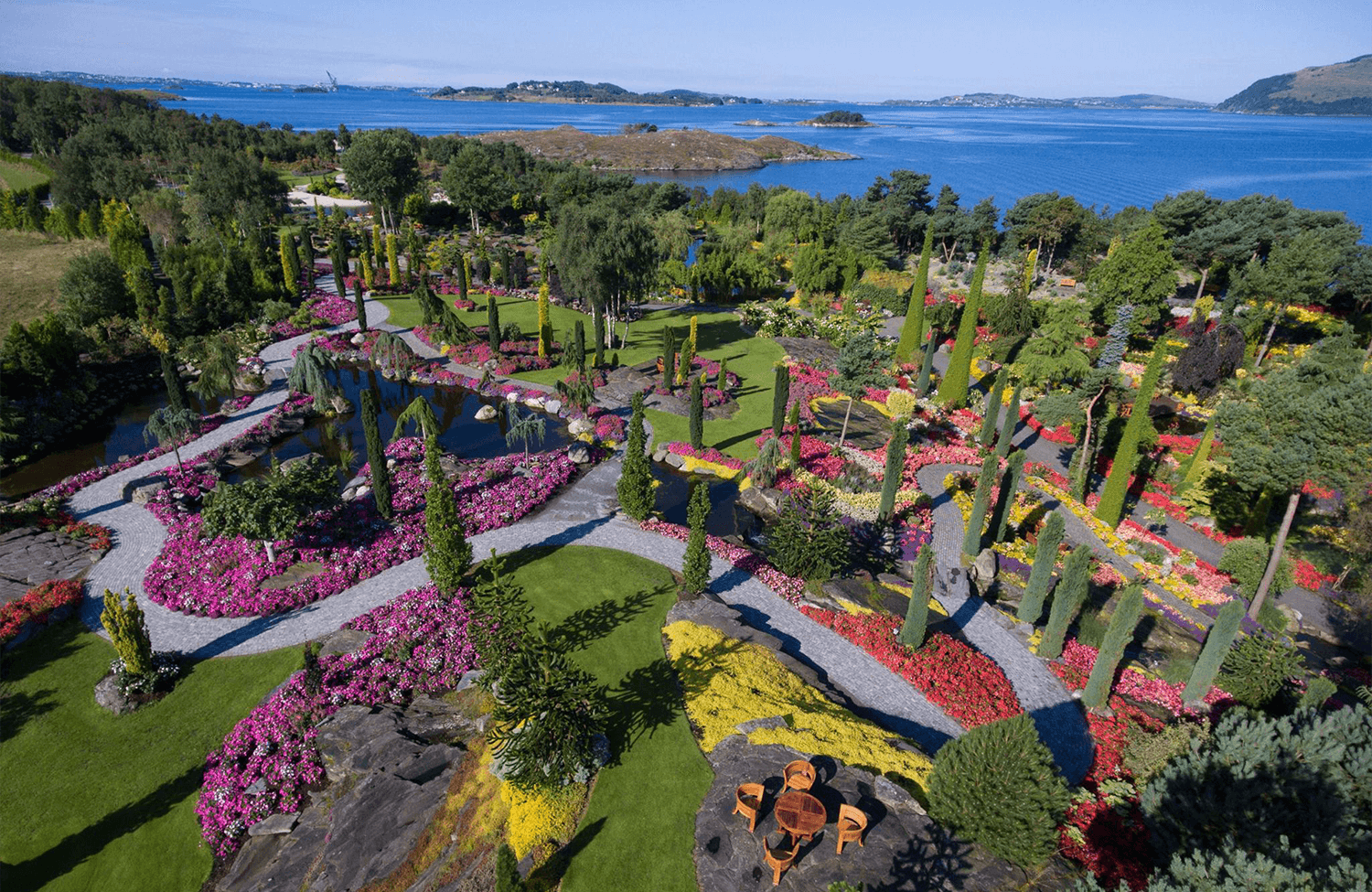

What emerged over the next eight years surprised even the family. The island sits in Boknafjorden, where maritime currents create a microclimate up to 4°C warmer than Stavanger, just 20 minutes away by boat. Combined with Åsmund's professional horticultural knowledge, this allowed palms, banana plants, and lemon trees to survive Norwegian winters. By the early 1990s, friends visiting the private garden urged the family to open commercially.

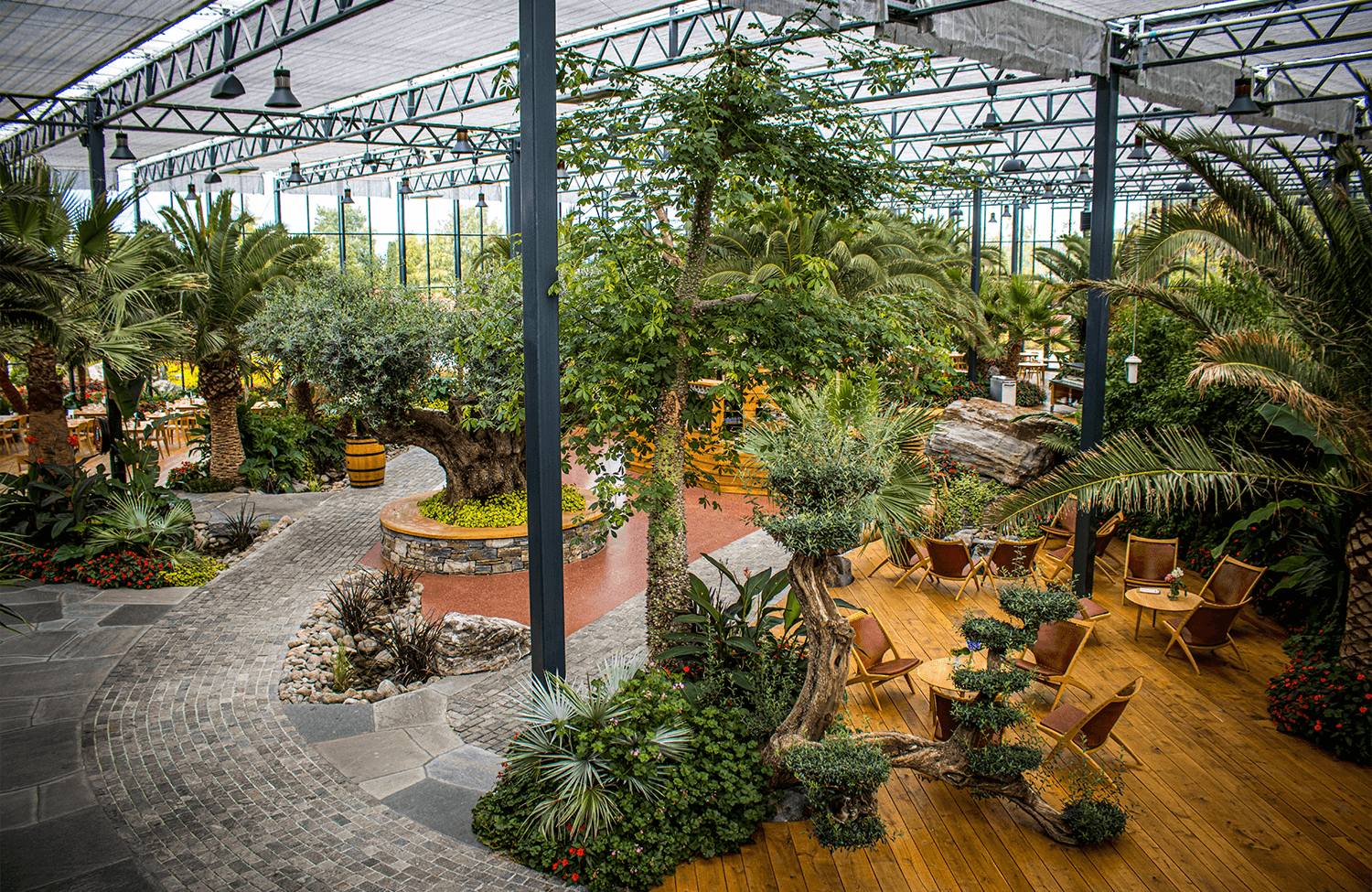

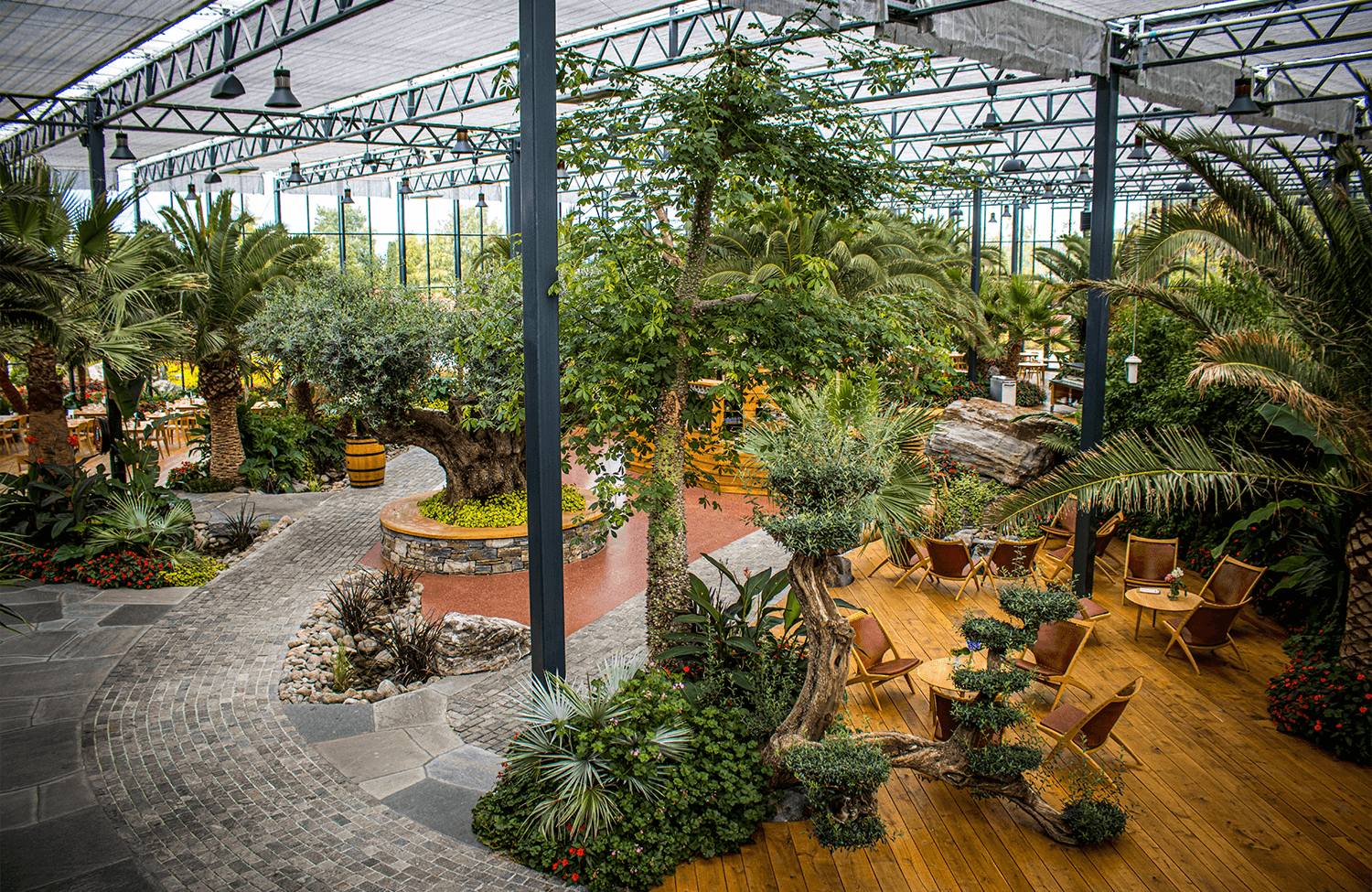

In 1995, Åsmund's son Olav and wife Siri launched Flora og Fjære as a public attraction. Their first season drew several hundred visitors. By year two, they had 10,000. The garden needed a revenue model, and they found one: make the restaurant essential, not optional. Third-generation owners Endre Bryn Hidlefjord and Hanne Kvernberg Hidlefjord now manage operations, with recent additions including a massive glass greenhouse and beach area with outdoor bar—infrastructure investments possible only because of the bundled model's guaranteed revenue per visitor.

The Economics of Mandatory Experiences

Here's what you actually get for that 1,890 NOK weekday ticket (or 2,190 NOK on Saturdays): round-trip ferry on the MS Rygerfjord catamaran, 40-minute guided tour led by family members, three-course meal by Chef André Mulder, and an hour of self-guided garden exploration. The experience lasts approximately five hours total. Drinks cost extra, and children ages 6-12 pay 890 NOK while kids under 5 get in for 250 NOK.

The family defends the bundled approach clearly on their website: "Our gardens would not exist without the restaurant and garden tour—and vice versa." This isn't marketing spin; it's operational reality. The garden requires year-round maintenance staff despite only operating mid-May through mid-September. Over 50,000 flowers are planted annually before opening day. Tropical plants need winter greenhouse protection. The restaurant generates revenue that gardening alone couldn't sustain.

But the mandatory model also serves strategic purposes. It controls visitor flow—no one lingers indefinitely when they have a scheduled boat departure. It prevents the place from becoming an Instagram selfie factory where crowds trample plantings. And it positions Flora og Fjære as an event rather than a garden, which justifies premium pricing and attracts corporate groups. The venue accommodates 25-600 people for events, with Queen Sonja having celebrated her 70th birthday there.

What Gets Lost in the Hype

The garden's promotional materials emphasize rarity and exoticism, and visitors do encounter plants that shouldn't survive at this latitude. Yet the "tropical paradise" framing glosses over limitations. Norwegian winters still require extensive protection systems. Some visitors report that while the garden impresses, the forced dining experience feels like paying for two attractions when you only wanted one. Others note that 40 minutes of guided tour isn't long enough to genuinely explore 12 acres—you get the highlight reel, not the deep botanical experience.

There's also the accessibility paradox. The family worked to make paths wheelchair-friendly with cobblestone paving, and the boat accommodates mobility devices. But the five-hour commitment, mandatory advance booking, and high price point exclude spontaneous visitors, budget travelers, and anyone who just wants a quick garden stroll. The business model that enables the garden's existence also limits who can experience it.

The marketing emphasizes family legacy and passion, which is genuine—third-generation involvement proves that. But it's equally a calculated tourism product that has evolved significantly from Åsmund's retirement hobby. Recent expansions like the glass greenhouse restaurant and beach bar represent substantial capital investment that only makes sense with guaranteed high-margin revenue from bundled experiences.

Why This Model Keeps Spreading

Flora og Fjære matters because it demonstrates how niche attractions survive in high-cost countries. Norway's wage levels and seasonal tourism windows make traditional "pay admission, maybe buy lunch" models economically unviable for private operators. By bundling experiences and controlling the entire visitor journey, the Bryn family created a sustainable business that also happens to preserve an unusual garden.

The approach has spread throughout Scandinavia: multi-hour "experience packages" replacing simple admission tickets, mandatory restaurant components, advance-only booking. Whether you see this as smart entrepreneurship or forced consumption depends on what you value. But 35,000 annual visitors suggest many travelers accept the trade-off: pay more, but ensure the thing you're paying for continues existing.