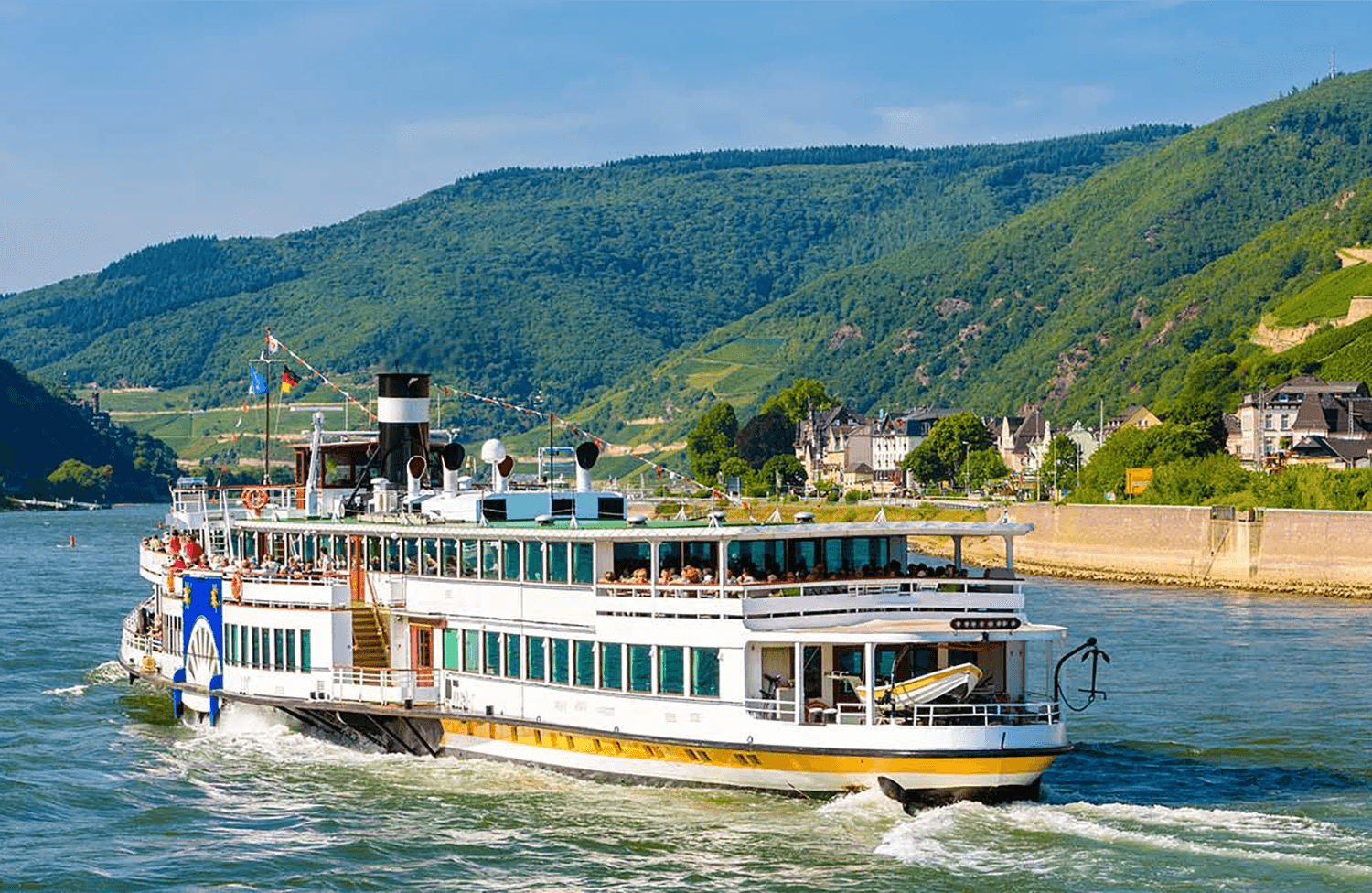

A Merchant's Nightmare: 24 Hours Shipping Wine Upstream on the 1400s Rhine

Dawn breaks over Cologne, and you're already calculating whether this journey will bankrupt you. Your barge, loaded with wine barrels from the Rhineland vineyards, needs to reach Mainz—just 150 kilometers upstream. Between you and profit stand 12 toll castles, each demanding payment. The math is brutal: at 8 denari per toll station, you'll surrender nearly 100 denari in silver before you're done. That's roughly 68 grams of pure silver, or about 15-20% of your cargo's value, extracted purely for the privilege of floating past medieval extortion operations disguised as fortresses.

It's 5 AM, and your two horses are already hitched to the towropes. This is how goods move upstream on the Rhine in the 15th century—not by sail or oar, but by horse-drawn towing along narrow paths carved into the riverbanks. Your horses will walk all day, pulling 40 times more weight than they could haul in a cart, yet you'll be lucky to cover 15 kilometers before nightfall. Towpath travel is slow, methodical work, and every kilometer costs money in feed and labor.

The First Castle Appears

By mid-morning, the first toll castle looms ahead. You can't see the chain yet, but you know it's there—a massive iron barrier ready to rise across the river if you dare pass without paying. The castle's design is no accident: positioned at a river narrow where dangerous currents force all traffic to one side, guards can trap any vessel that refuses to pay. The toll booth sits at water level, connected to the fortress above by defensive walls. Armed men watch from the ramparts.

You dock at the customs house and hand over your first payment. The toll collector barely glances at your manifest—he's done this a thousand times. Eight denari disappear into his lockbox. You're back on the water within an hour, but this scene will repeat 11 more times before Mainz. The cumulative delay is worse than the cost. Those hours spent paying tolls, waiting in line behind other merchants, and dealing with corrupt officials who "discover" additional fees—they add days to your journey.

Why Submit to This Madness?

The alternative is worse. Road transport costs three times as much as river shipping—1.5 pence per mile versus 0.5 pence by water for a ton of grain in the early 14th century. Your wine shipment would bankrupt you on land. The Rhine, for all its toll stations, remains the cheapest option. Besides, the 1250 Holy Roman Empire theoretically limited these extractions. Between Mainz and Cologne, Emperor Frederick II permitted just 12 official toll stations. Greedy local princes wanted more, but imperial law—at least on paper—held them back from complete chaos.

Your horses plod on. By evening, you've passed three more castles and paid three more tolls. You're 45 kilometers from Cologne, nowhere near Mainz, and camping on the riverbank for the night. Tomorrow brings more of the same: slow progress, more tolls, more calculations about whether the profit margin will survive this journey.

What Those Castles Really Were

Modern tourists photograph these Rhine castles as romantic medieval architecture. They were toll booths—armed, fortified, and ruthlessly efficient at extracting money. In the 14th century, 62 customs stations operated on the Rhine, each controlled by a different prince, bishop, or noble who'd secured the right from the Emperor. The system was so profitable that church officials fought over toll rights, with Pope John XXII attempting to excommunicate rulers who threatened episcopal toll revenues.

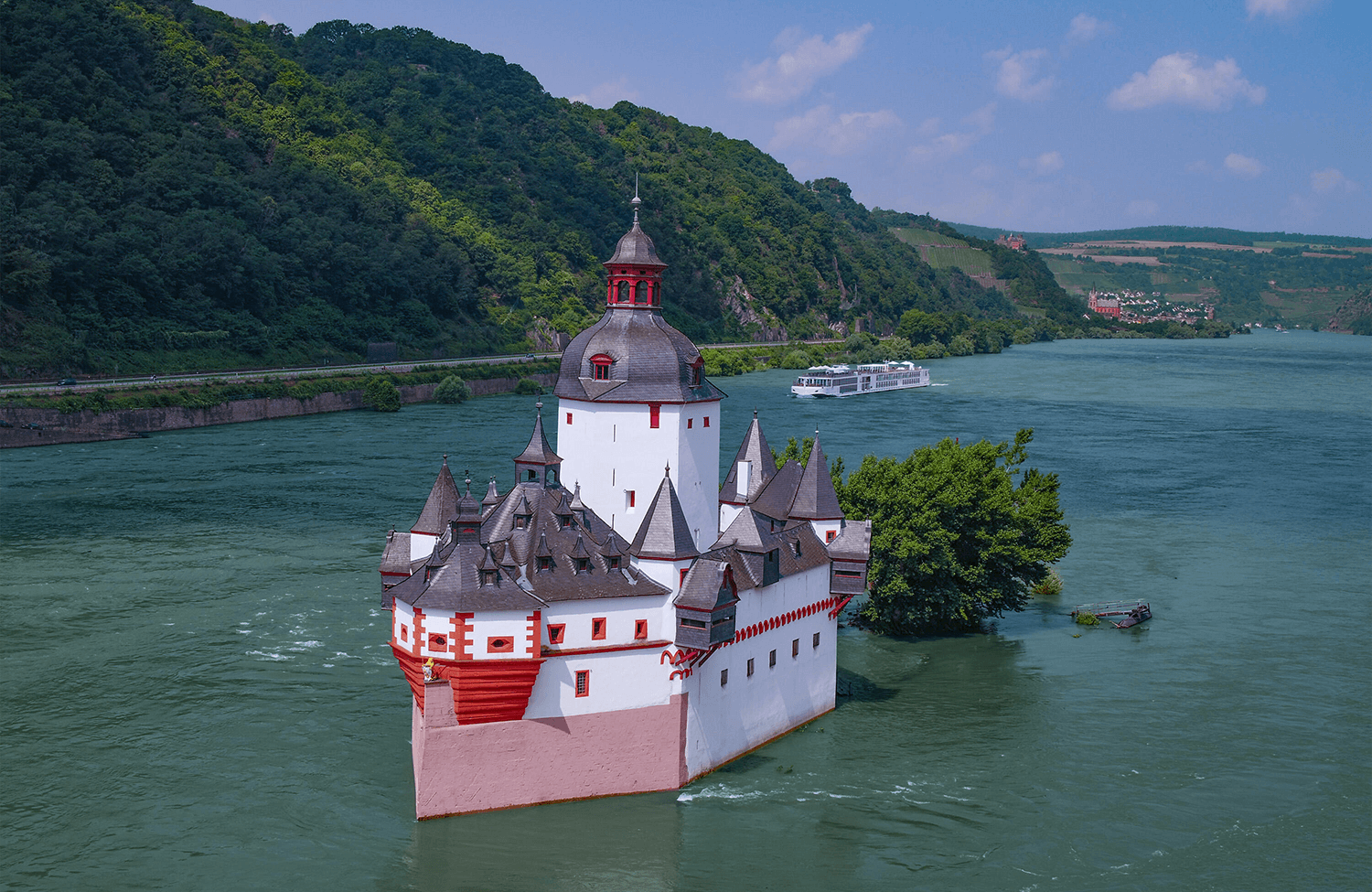

The castles that survived into the 1800s weren't the strongest militarily—they were the ones positioned at geographic chokepoints where merchants couldn't evade payment. Pfalzgrafenstein Castle, built on an island in 1326, could stretch chains across the river's narrow passage and imprison crews who refused to pay in a dungeon that was literally a wooden raft floating in a well.

Why It Matters

This wasn't ancient history when those castles were built—it was a functioning commercial system that shaped European trade for centuries. River tolls only ended in 1867 when a unified Germany finally abolished them. Until then, Rhine commerce meant accepting that a significant portion of your profits would vanish into feudal pockets, simply for the privilege of using Europe's most important waterway. Next time you're on a Rhine cruise, remember: those picturesque castles tourists photograph were medieval Europe's version of highway robbery, just with prettier architecture and better PR.